In January, Silas and I took a mini-break down to Las Cruces. We stayed at the Hotel Encanto de Las Cruces. It might look like a generic airport hotel from the outside, but once inside there is a stunning courtyard oasis and pool perched on a hill overlooking the city and mountains beyond.

We wandered the farmer’s market and went for a beautiful hike in the Organ Mountains on our first day. Snow clung to the shady side of the mountains, tucked under tree branches, but the trails were clear for the most part.

The next day we headed towards Alamagordo, to White Sands, which had become a national park since our last visit.

In the heart of the Tularosa Basin, the world’s largest gypsum dune field covers 275 square miles, forming shapes dependent on winds and not tides. Soaptree yuccas line the road, in places growing an elongated stem to reach above the gypsum as it drifts. It is a sea of sand, next to the White Sands Missile Range, about seventy miles from the Trinity Site, where the first atomic bomb was detonated on July 16, 1945. Signs led us into the park, noting the possibility of temporary closures for US military testing, and reminding us that the missile range is still active.

At the trailhead, signs warned us in English and Spanish to Stay Alive, Bring lots of water, Wear sunscreen, Pack layers. Which is basic desert logic. And there was more, an adjacent sign said, Know before you go, Alkali Flat Trail, This trail is not flat!, Do not touch any strange objects, sometimes military planes drop dangerous objects on our dunes, and Do not rely on GPS to find your way, sometimes military tests disrupt satellite signals for hours. There was no pretending that we weren’t hiking right next to an active missile range, no matter how beautiful it is.

At the base of most dunes, the sand changes. The interdune landscape. Harder underfoot, it holds in more moisture than the sand at the crest, and a handful of plants take advantage, Torrey’s jointfir, Ephedra torreyana, a small shrub shooting its roots down 6 feet into the gypsum, chamisa, and clusters of grass all trying to hold on in spite of the shifting sands.

Here, in the Alkali Flat, researchers have found the largest known field of Pleistocene ice age trackways. Dire wolf, ancient bison, saber-tooth cat, giant ground sloth, and mammoth all walked here and left impressions behind from 19,000-40,000 years ago. Ghost tracks occur just below the surface, only rarely appearing when a salt hollow forms above them. They can be detected with ground-penetrating radar and magnetic surveys. Raised prints left in mud were filled in with a stronger mineral, dolomite, that lasted long after the softer materials eroded away. And a third kind, ancient prints left in mud and filled in with sand can still be found. On the western playa, human footprints were found in a trench. Ancient grass seeds, Ruppia cirrhosa, were among in the sediment layers above and below. With radiocarbon dating, researchers recently learned they were from 22,806 and 21,130 years ago, far earlier than the previous estimates of humans in North America from 13,500-16,000 years ago. (for more info see nps.gov )

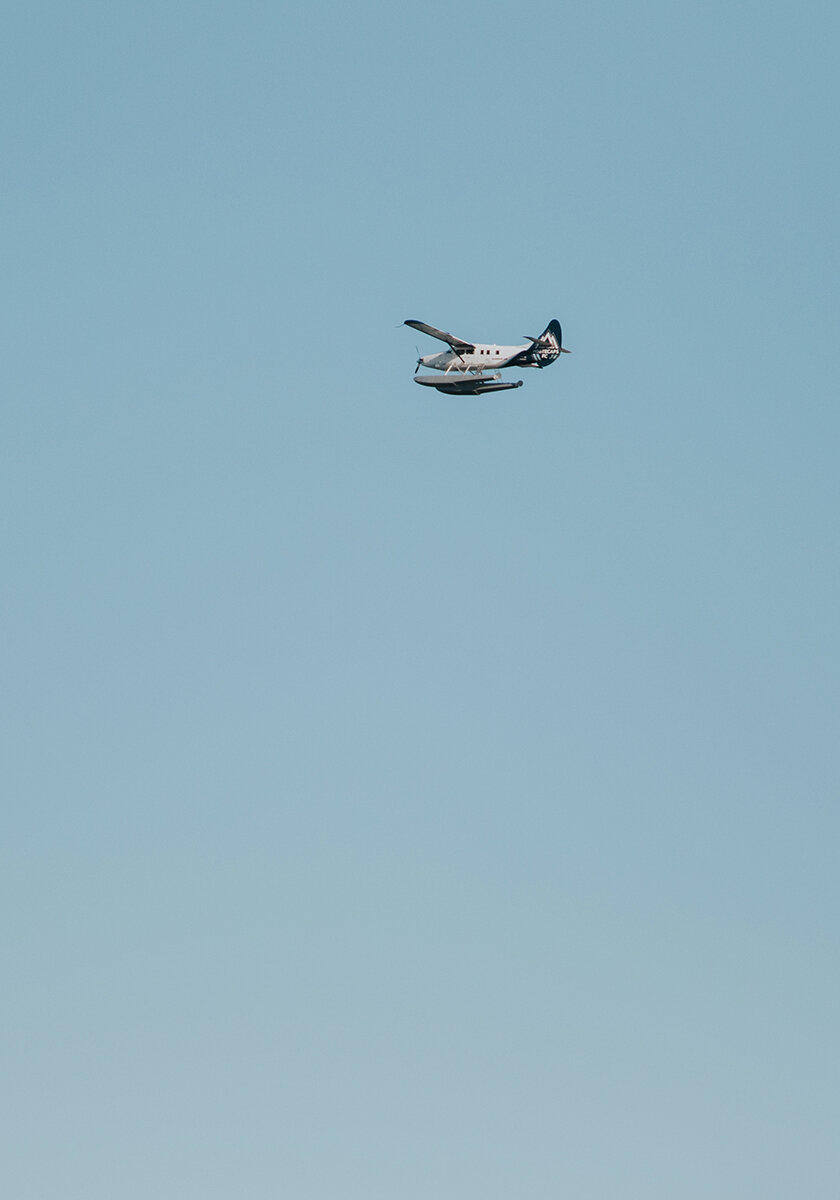

all photographs by me, Becca Grady, 2023